40 targets. 80+ arrows. Two hours of intense concentration.

40 targets. 80+ arrows. Two hours of intense concentration.

At first, a stroll around the woods on a sunny day shooting at a few rubber creatures had sounded like a pretty gentle way to spend a morning. In practice, it was exhausting.

This was to be my fourth archery training session. These took place on Sunday mornings – mostly just for convenience, I imagine, although looking around at the men gathered there (all men, so far), and being the nerd that I am, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Edward III’s Archery Law of 1363. That had required all able-bodied male subjects to practice archery for at least two hours every Sunday under the supervision of the local clergy.

No clergy here today, as far as I’m aware. Not unless you count Nev – which I kind of do. He is my archery coach, and my Jedi master.

For a variety of reasons – prior commitments, atrocious weather – I’d missed a few weeks here and there, and as a result it had taken a couple of months to get to this point. But after today – unless I let the side down by impaling myself or killing someone – I would be “signed off” by coach Nev. That meant becoming a full member of the club, and also that I could join the National Field Archery Society. More importantly, it also meant being entrusted with the number for the combination lock on the gate, so I could come here and shoot a few arrows whenever I wished.

I’ve never been much of a joiner [insert woodworking-based joke here]. Never one to hanker after the key to the executive washroom or an invitation to join the Masons. But somehow, I relished this prospect. This knocked attempts at social advancement into a cocked hat. From 40 yards. With lethal velocity.

That archery is a broad church is graphically demonstrated by the two men who stroll over to chat to me before the session begins. One is carrying a contraption that looks less like a bow than something he should get on and ride (in fact, I swear the bike I rode here today has fewer moving parts). The other is a bare stick with a string – AKA a classic, medieval-style longbow. It’s to the latter style of archery that I aspire – that was and is my inspiration. But today I’ve come armed with a bow that is neither one nor the other. Yes, I’ve bought my own. And no, it’s not a longbow – not yet.

I’ll explain.

Archery is stupidly simple and hellishly complicated. Everyone knows the principle, and probably most could make a decent job of getting an arrow to fly from a bow, even if it did miss the barn door they were aiming at and took their ear off in the process. Even with the most complex of bows, it’s obvious what’s going on. You pull that and let it go and that other bit goes over there. Simple. A child can do it. But refining that into something you can precisely control – taking into account all the variables and taming awesome forces, turning it into an art – that is hard.

And yet, as Nev has explained repeatedly over past weeks, beyond certain preparatory factors such as posture and grip, there are really only four parts to the process of archery. Aim. Draw. Anchor. Release.

Let’s break that down.

A hedge is not recommended as a backstop

Aim

You hold the bow with the arrow nocked ready on the string, pointing where you want it to go. In barebow shooting – which is what this is – there is no sight on the bow, and no part of either it or the arrow is visually lined up with your target. You look beyond the bow, beyond the arrow, aiming instinctively, with eyes only for the place you intend that arrow to strike.

Draw

With your forefinger above the arrow nock and next two fingers below – the classic draw familiar to medieval archers, known as Mediterranean Loose – you pull back the string and the arrow, your elbow sufficiently raised that the forearm is in perfect alignment with the arrow and your bow arm, so all describe a complete straight line.

Anchor

You bring your drawing hand to a fixed point where it briefly stops before the moment of release. This is the point of full draw – the apex of the whole movement, beyond which it must not go. In traditional European archery, the index finger of the drawing hand typically anchors at the corner of the mouth, the string just touching the cheek. This is what works for me. There are different variations and styles, and different techniques work for different archers, but the key factor is that once you have found your preferred anchor point, it should always be the same. In archery, consistency is everything.

Release

You let go. This, perhaps the simplest action of all, is also the toughest to get right. With such pressure on the fingers, simply letting go is difficult. You end up plucking the string instead of simply releasing it. It thrums loudly, and the twist of the string as it rolls off your fingers sends your arrow off to the left of your intended target. You immediately know you’ve got it right, however. It’s like when you hit a ball right in the middle of the bat. The sound is good. The movement seems effortless. In archery, you know this one is going where you want before it gets there. And if you release it the right way, your draw hand naturally follows through, continuing back past your ear as the pressure is released. That is a sign all is well.

Once you have mastered each of these steps you have all the tools to be a great archer, and there is absolutely no reason why you cannot grasp them in your very first session. As with dance, however, it’s putting the steps together that is the real art. Like dance, it is a question of balance, and of rhythm. You need to find the right balance between instinct and control, and strike the right rhythm so each of the steps flows naturally one into the other. Too fast, too impatient, and it’s a snap shot – pure instinct, but with little control. You might be lucky and hit your target. It might even be a great shot – but you won’t know how to reproduce it. Take too long, and too much thought gets into the process. You tense. You dither. You glance at your arrow point and your brain tells you to raise it up, because where instinct has placed it looks like it must be too low – and your arrow sails way over the top of the target.

Nearly every time I shot with Nev at my shoulder, I was falling short with one or more of these four elements. I was focusing on my release and forgot to anchor properly. I concentrated on the anchor and let my aim waver. Then, trying to get every part right, I’d take far too long, and think far too much, and the whole shot would go to pot. But somewhere between trying and not trying, between thought and instinct, there is success. Every once in a while, I’d get it. And when you achieve that, it’s glorious.

Such moments were rare, and after the first two sessions, I became frustrated. I knew that practicing this for just a couple of hours a week – or every few weeks, as it was turning out – was not enough. I needed my own bow.

I had been learning with basic recurve belonging to the club which had a 20lb draw weight. This is low, but good for a beginner as it allows you to focus on technique rather than fretting about how hard it is to heave the string. For my own bow – what I was already thinking of as my “practice bow” – it made sense to get one that was as close to this as possible. Perhaps a little stronger to take me up a notch, but not to be so powerful that I couldn’t safely shoot in the corner of the garden I had set aside for it.

Such recurve bows are relatively cheap – you can get a decent entry level one for about £50 – and many good archery suppliers will do a package which provides everything you need to get started: arrows, quiver, arm guard, leather tab to protect the fingers and so on. Because these packages have been put together by professionals who know their stuff, you’re also spared the hassles of setting up the bow correctly (the string has nocking points for the arrows fitted in the right place, for example) and the arrows are matched to the bow (matching arrows to your bow, I have discovered, is a sacred mystery more arcane than a medieval alchemical treatise).

Another great advantage of this type of recurve is that it is a “takedown”; the limbs detach and it breaks down into three parts which can be packed into a bag. That would mean I could easily sling it on my back and bike to the woods to practice.

Easton Jazz arrows – archery like it’s 1985

So, in went the order to Archery World. And, a couple of days later, I was the proud owner of a 30lb, 68” recurve and all the (very basic) kit, including eight aluminium arrows. The quiver isn’t going to win any fashion awards. The arm guard – plastic – looks like something out of a Christmas cracker. And, as if to further emphasise that you’re still just a kid playing at this game, the arrows – less sharp than a knitting needle – are called “Jazz” and come in a tasteful metallic purple.

But put aside notions of this being the My Little Pony version. The arrows are made by Easton, who turn out professional tournament arrows. And when you shoot one – or, more likely, when you find yourself trying to heave it from some bit of wood in which it’s got embedded, because you missed what you were aiming at – it’s instantly clear this is not a toy.

Only the sight goes straight in the bin. Not that it’s bad – I just have no use for it.

Only the sight goes straight in the bin. Not that it’s bad – I just have no use for it.

By the time I get to the session, I’ve upgraded the tab and replaced the arm guard with a decent leather bracer. I’ve also been practicing – which has mainly involved destroying a cardboard box stuffed with packing material (and part of my garden gate – collateral damage). I feel slightly less like a kid. Slightly less like I’m playing. And so, Nev takes me round my first bona fide field archery course.

It’s an education, for sure. Targets are mostly 3D and in the shape of some animal or other. There’s a boar. A capercaillie. Some kind of low-lying weasel/stoat/ferret thing. Also some creatures you would necessarily expect to find yourself shooting at. A hawk. A couple of owls. A somewhat oversized frog. And, my personal favourite, a hyena. Several times, I manage to place all my arrows around him, and not in him. “That hyena’s laughing at me,” I say. Nev smirks and gestures for me to get on with it.

There are forty targets in all – although in reality this means a dozen or so positioned around the woods that we revisit in different combinations. You have up to three arrows to shoot at each. If you hit it with your first shot (20 points for a “kill”, 16 for a “wound”), you’re done, and you move on to the next. If you miss, you move to a peg closer to the target and try again. Miss with all three arrows, and you get zero.

As we move around, shooting from different angles, different heights, between trees, the members of this strange menagerie start to become familiar. I greet them like old friends – then take a strange delight in shooting them. All are different shapes and sizes. Some are upright and present a narrow target. Perhaps surprisingly, these are not the hardest to hit. Toughest are those that are lowest to the ground – and somewhat paradoxically, the closer you get to them, the harder the shot gets. The angle that exists between your eye and the arrow, and which you learn to take into account when shooting from a distance, is totally wrong close up. The smallest target – the frog – eludes my arrow point for most of the morning. But finally, the frog croaks. It’s the big goodnight for the owls. Even the hyena has the smile wiped off its face. Only the low-lying weasel/stoat/ferret thing – the flattest target of all – eludes me completely. I’ll have him one day…

At the end, my score is 378. I’ll leave you to work out what it could have been with a perfect round. Nev calls it a respectable score, but I’m not sure if this is kindness to a newbie, or massive understatement. Or something in between. I’ll take it, though. My brain and my body are drained and I have a love-bite from my bow where the position of the bracer wasn’t quite right, but before I leave to collapse into a heap there’s one more task to perform. This is the boring bit. Except it isn’t. It’s the bit that, in a way, I am most excited about. I fill in some forms. And I’m in – my place earned, an accepted member of this merry band.

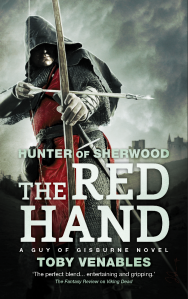

Time to order the longbow.